Television (TV) is a telecommunication medium for transmitting moving images and sound. Additionally, the term can refer to a physical television set rather than the medium of transmission. Television is a mass medium for advertising, entertainment, news, and sports. The medium is capable of more than “radio broadcasting,” which refers to an audio signal sent to radio receivers.

Television became available in crude experimental forms in the 1920s, but only after several years of further development was the new technology marketed to consumers. After World War II, an improved form of black-and-white television broadcasting became popular in the United Kingdom and the United States, and television sets became commonplace in homes, businesses, and institutions. During the 1950s, television was the primary medium for influencing public opinion.[1] In the mid-1960s, color broadcasting was introduced in the U.S. and most other developed countries.

The availability of various types of archival storage media such as Betamax and VHS tapes, LaserDiscs, high-capacity hard disk drives, CDs, DVDs, flash drives, high-definition HD DVDs and Blu-ray Discs, and cloud digital video recorders has enabled viewers to watch pre-recorded material—such as movies—at home on their own time schedule. For many reasons, especially the convenience of remote retrieval, the storage of television and video programming now also occurs on the cloud (such as the video-on-demand service by Netflix). At the beginning of the 2010s, digital television transmissions greatly increased in popularity. Another development was the move from standard-definition television (SDTV) (576i, with 576 interlaced lines of resolution and 480i) to high-definition television (HDTV), which provides a resolution that is substantially higher. HDTV may be transmitted in different formats: 1080p, 1080i and 720p. Since 2010, with the invention of smart television, Internet television has increased the availability of television programs and movies via the Internet through streaming video services such as Netflix, Amazon Prime Video, iPlayer and Hulu.

In 2013, 79% of the world’s households owned a television set.[2] The replacement of earlier cathode-ray tube (CRT) screen displays with compact, energy-efficient, flat-panel alternative technologies such as LCDs (both fluorescent-backlit and LED), OLED displays, and plasma displays was a hardware revolution that began with computer monitors in the late 1990s. Most television sets sold in the 2000s were still CRT, it was only in early 2010s that flat-screen TVs decisively overtook CRT.[3] Major manufacturers announced the discontinuation of CRT, Digital Light Processing (DLP), plasma, and even fluorescent-backlit LCDs by the mid-2010s.[4][5] LEDs are being gradually replaced by OLEDs.[6] Also, major manufacturers have started increasingly producing smart TVs in the mid-2010s.[7][8][9] Smart TVs with integrated Internet and Web 2.0 functions became the dominant form of television by the late 2010s.[10][better source needed]

Television signals were initially distributed only as terrestrial television using high-powered radio-frequency television transmitters to broadcast the signal to individual television receivers. Alternatively, television signals are distributed by coaxial cable or optical fiber, satellite systems, and, since the 2000s, via the Internet. Until the early 2000s, these were transmitted as analog signals, but a transition to digital television was expected to be completed worldwide by the late 2010s. A standard television set consists of multiple internal electronic circuits, including a tuner for receiving and decoding broadcast signals. A visual display device that lacks a tuner is correctly called a video monitor rather than a television.

The television broadcasts are mainly a simplex broadcast meaning that the transmitter cannot receive and the receiver cannot transmit.

Etymology

The word television comes from Ancient Greek τῆλε (tele) ‘far’ and Latin visio ‘sight’. The first documented usage of the term dates back to 1900, when the Russian scientist Constantin Perskyi used it in a paper that he presented in French at the first International Congress of Electricity, which ran from 18 to 25 August 1900 during the International World Fair in Paris.

The anglicized version of the term is first attested in 1907, when it was still “…a theoretical system to transmit moving images over telegraph or telephone wires“.[11] It was “…formed in English or borrowed from French télévision.”[11] In the 19th century and early 20th century, other “…proposals for the name of a then-hypothetical technology for sending pictures over distance were telephote (1880) and televista (1904).”[11]

The abbreviation TV is from 1948. The use of the term to mean “a television set” dates from 1941.[11] The use of the term to mean “television as a medium” dates from 1927.[11]

The term telly is more common in the UK. The slang term “the tube” or the “boob tube” derives from the bulky cathode-ray tube used on most TVs until the advent of flat-screen TVs. Another slang term for the TV is “idiot box.”[12]

History

Main article: History of television

Mechanical

Main article: Mechanical television

Facsimile transmission systems for still photographs pioneered methods of mechanical scanning of images in the early 19th century. Alexander Bain introduced the facsimile machine between 1843 and 1846. Frederick Bakewell demonstrated a working laboratory version in 1851.[citation needed] Willoughby Smith discovered the photoconductivity of the element selenium in 1873. As a 23-year-old German university student, Paul Julius Gottlieb Nipkow proposed and patented the Nipkow disk in 1884 in Berlin.[13] This was a spinning disk with a spiral pattern of holes, so each hole scanned a line of the image. Although he never built a working model of the system, variations of Nipkow’s spinning-disk “image rasterizer” became exceedingly common.[14] Constantin Perskyi had coined the word television in a paper read to the International Electricity Congress at the International World Fair in Paris on 24 August 1900. Perskyi’s paper reviewed the existing electromechanical technologies, mentioning the work of Nipkow and others.[15] However, it was not until 1907 that developments in amplification tube technology by Lee de Forest and Arthur Korn, among others, made the design practical.[16]

The first demonstration of the live transmission of images was by Georges Rignoux and A. Fournier in Paris in 1909. A matrix of 64 selenium cells, individually wired to a mechanical commutator, served as an electronic retina. In the receiver, a type of Kerr cell modulated the light, and a series of differently angled mirrors attached to the edge of a rotating disc scanned the modulated beam onto the display screen. A separate circuit regulated synchronization. The 8×8 pixel resolution in this proof-of-concept demonstration was just sufficient to clearly transmit individual letters of the alphabet. An updated image was transmitted “several times” each second.[17]

In 1911, Boris Rosing and his student Vladimir Zworykin created a system that used a mechanical mirror-drum scanner to transmit, in Zworykin’s words, “very crude images” over wires to the “Braun tube” (cathode-ray tube or “CRT”) in the receiver. Moving images were not possible because, in the scanner: “the sensitivity was not enough and the selenium cell was very laggy”.[18]

In 1921, Édouard Belin sent the first image via radio waves with his belinograph.[19]

By the 1920s, when amplification made television practical, Scottish inventor John Logie Baird employed the Nipkow disk in his prototype video systems. On 25 March 1925, Baird gave the first public demonstration of televised silhouette images in motion at Selfridges‘s department store in London.[20] Since human faces had inadequate contrast to show up on his primitive system, he televised a ventriloquist’s dummy named “Stooky Bill,” whose painted face had higher contrast, talking and moving. By 26 January 1926, he had demonstrated before members of the Royal Institution the transmission of an image of a face in motion by radio. This is widely regarded as the world’s first true public television demonstration, exhibiting light, shade, and detail.[21] Baird’s system used the Nipkow disk for both scanning the image and displaying it. A brightly illuminated subject was placed in front of a spinning Nipkow disk set with lenses that swept images across a static photocell. The thallium sulfide (thalofide) cell, developed by Theodore Case in the U.S., detected the light reflected from the subject and converted it into a proportional electrical signal. This was transmitted by AM radio waves to a receiver unit, where the video signal was applied to a neon light behind a second Nipkow disk rotating synchronized with the first. The brightness of the neon lamp was varied in proportion to the brightness of each spot on the image. As each hole in the disk passed by, one scan line of the image was reproduced. Baird’s disk had 30 holes, producing an image with only 30 scan lines, just enough to recognize a human face.[22] In 1927, Baird transmitted a signal over 438 miles (705 km) of telephone line between London and Glasgow.[23] Baird’s original ‘televisor’ now resides in the Science Museum, South Kensington.

In 1928, Baird’s company (Baird Television Development Company/Cinema Television) broadcast the first transatlantic television signal between London and New York and the first shore-to-ship transmission. In 1929, he became involved in the first experimental mechanical television service in Germany. In November of the same year, Baird and Bernard Natan of Pathé established France’s first television company, Télévision-Baird-Natan. In 1931, he made the first outdoor remote broadcast of The Derby.[24] In 1932, he demonstrated ultra-short wave television. Baird’s mechanical system reached a peak of 240 lines of resolution on BBC telecasts in 1936, though the mechanical system did not scan the televised scene directly. Instead, a 17.5 mm film was shot, rapidly developed, and then scanned while the film was still wet. [citation needed]

A U.S. inventor, Charles Francis Jenkins, also pioneered the television. He published an article on “Motion Pictures by Wireless” in 1913, transmitted moving silhouette images for witnesses in December 1923, and on 13 June 1925, publicly demonstrated synchronized transmission of silhouette pictures. In 1925, Jenkins used the Nipkow disk and transmitted the silhouette image of a toy windmill in motion over a distance of 5 miles (8 km), from a naval radio station in Maryland to his laboratory in Washington, D.C., using a lensed disk scanner with a 48-line resolution.[25][26] He was granted U.S. Patent No. 1,544,156 (Transmitting Pictures over Wireless) on 30 June 1925 (filed 13 March 1922).[27]

Herbert E. Ives and Frank Gray of Bell Telephone Laboratories gave a dramatic demonstration of mechanical television on 7 April 1927. Their reflected-light television system included both small and large viewing screens. The small receiver had a 2-inch-wide by 2.5-inch-high screen (5 by 6 cm). The large receiver had a screen 24 inches wide by 30 inches high (60 by 75 cm). Both sets could reproduce reasonably accurate, monochromatic, moving images. Along with the pictures, the sets received synchronized sound. The system transmitted images over two paths: first, a copper wire link from Washington to New York City, then a radio link from Whippany, New Jersey. Comparing the two transmission methods, viewers noted no difference in quality. Subjects of the telecast included Secretary of Commerce Herbert Hoover. A flying-spot scanner beam illuminated these subjects. The scanner that produced the beam had a 50-aperture disk. The disc revolved at a rate of 18 frames per second, capturing one frame about every 56 milliseconds. (Today’s systems typically transmit 30 or 60 frames per second, or one frame every 33.3 or 16.7 milliseconds, respectively.) Television historian Albert Abramson underscored the significance of the Bell Labs demonstration: “It was, in fact, the best demonstration of a mechanical television system ever made to this time. It would be several years before any other system could even begin to compare with it in picture quality.”[28]

In 1928, WRGB, then W2XB, was started as the world’s first television station. It broadcast from the General Electric facility in Schenectady, NY. It was popularly known as “WGY Television.” Meanwhile, in the Soviet Union, Leon Theremin had been developing a mirror drum-based television, starting with 16 lines resolution in 1925, then 32 lines, and eventually 64 using interlacing in 1926. As part of his thesis, on 7 May 1926, he electrically transmitted and then projected near-simultaneous moving images on a 5-square-foot (0.46 m2) screen.[26]

By 1927 Theremin had achieved an image of 100 lines, a resolution that was not surpassed until May 1932 by RCA, with 120 lines.[29]

On 25 December 1926, Kenjiro Takayanagi demonstrated a television system with a 40-line resolution that employed a Nipkow disk scanner and CRT display at Hamamatsu Industrial High School in Japan. This prototype is still on display at the Takayanagi Memorial Museum in Shizuoka University, Hamamatsu Campus. His research in creating a production model was halted by the SCAP after World War II.[30]

Because only a limited number of holes could be made in the disks, and disks beyond a certain diameter became impractical, image resolution on mechanical television broadcasts was relatively low, ranging from about 30 lines up to 120 or so. Nevertheless, the image quality of 30-line transmissions steadily improved with technical advances, and by 1933 the UK broadcasts using the Baird system were remarkably clear.[31] A few systems ranging into the 200-line region also went on the air. Two of these were the 180-line system that Compagnie des Compteurs (CDC) installed in Paris in 1935 and the 180-line system that Peck Television Corp. started in 1935 at station VE9AK in Montreal.[32][33] The advancement of all-electronic television (including image dissectors and other camera tubes and cathode-ray tubes for the reproducer) marked the start of the end for mechanical systems as the dominant form of television. Mechanical television, despite its inferior image quality and generally smaller picture, would remain the primary television technology until the 1930s. The last mechanical telecasts ended in 1939 at stations run by a lot of public universities in the United States.

Electronic

Further information: Video camera tube

In 1897, English physicist J. J. Thomson was able, in his three well-known experiments, to deflect cathode rays, a fundamental function of the modern cathode-ray tube (CRT). The earliest version of the CRT was invented by the German physicist Ferdinand Braun in 1897 and is also known as the “Braun” tube.[34] It was a cold-cathode diode, a modification of the Crookes tube, with a phosphor-coated screen. Braun was the first to conceive the use of a CRT as a display device.[35] The Braun tube became the foundation of 20th century television.[36] In 1906 the Germans Max Dieckmann and Gustav Glage produced raster images for the first time in a CRT.[37] In 1907, Russian scientist Boris Rosing used a CRT in the receiving end of an experimental video signal to form a picture. He managed to display simple geometric shapes onto the screen.[38]

In 1908, Alan Archibald Campbell-Swinton, a fellow of the Royal Society (UK), published a letter in the scientific journal Nature in which he described how “distant electric vision” could be achieved by using a cathode-ray tube, or Braun tube, as both a transmitting and receiving device,[39][40] he expanded on his vision in a speech given in London in 1911 and reported in The Times[41] and the Journal of the Röntgen Society.[42][43] In a letter to Nature published in October 1926, Campbell-Swinton also announced the results of some “not very successful experiments” he had conducted with G. M. Minchin and J. C. M. Stanton. They had attempted to generate an electrical signal by projecting an image onto a selenium-coated metal plate that was simultaneously scanned by a cathode ray beam.[44][45] These experiments were conducted before March 1914, when Minchin died,[46] but they were later repeated by two different teams in 1937, by H. Miller and J. W. Strange from EMI,[47] and by H. Iams and A. Rose from RCA.[48] Both teams successfully transmitted “very faint” images with the original Campbell-Swinton’s selenium-coated plate. Although others had experimented with using a cathode-ray tube as a receiver, the concept of using one as a transmitter was novel.[49] The first cathode-ray tube to use a hot cathode was developed by John B. Johnson (who gave his name to the term Johnson noise) and Harry Weiner Weinhart of Western Electric, and became a commercial product in 1922.[citation needed]

In 1926, Hungarian engineer Kálmán Tihanyi designed a television system using fully electronic scanning and display elements and employing the principle of “charge storage” within the scanning (or “camera”) tube.[50][51][52][53] The problem of low sensitivity to light resulting in low electrical output from transmitting or “camera” tubes would be solved with the introduction of charge-storage technology by Kálmán Tihanyi beginning in 1924.[54] His solution was a camera tube that accumulated and stored electrical charges (“photoelectrons”) within the tube throughout each scanning cycle. The device was first described in a patent application he filed in Hungary in March 1926 for a television system he called “Radioskop”.[55] After further refinements included in a 1928 patent application,[54] Tihanyi’s patent was declared void in Great Britain in 1930,[56] so he applied for patents in the United States. Although his breakthrough would be incorporated into the design of RCA‘s “iconoscope” in 1931, the U.S. patent for Tihanyi’s transmitting tube would not be granted until May 1939. The patent for his receiving tube had been granted the previous October. Both patents had been purchased by RCA prior to their approval.[57][58] Charge storage remains a basic principle in the design of imaging devices for television to the present day.[55] On 25 December 1926, at Hamamatsu Industrial High School in Japan, Japanese inventor Kenjiro Takayanagi demonstrated a TV system with a 40-line resolution that employed a CRT display.[30] This was the first working example of a fully electronic television receiver and Takayanagi’s team later made improvements to this system parallel to other television developments.[59] Takayanagi did not apply for a patent.[60]

In the 1930s, Allen B. DuMont made the first CRTs to last 1,000 hours of use, one of the factors that led to the widespread adoption of television.[61]

On 7 September 1927, U.S. inventor Philo Farnsworth‘s image dissector camera tube transmitted its first image, a simple straight line, at his laboratory at 202 Green Street in San Francisco.[62][63] By 3 September 1928, Farnsworth had developed the system sufficiently to hold a demonstration for the press. This is widely regarded as the first electronic television demonstration.[63] In 1929, the system was improved further by eliminating a motor generator so that his television system had no mechanical parts.[64] That year, Farnsworth transmitted the first live human images with his system, including a three and a half-inch image of his wife Elma (“Pem”) with her eyes closed (possibly due to the bright lighting required).[65]

Meanwhile, Vladimir Zworykin also experimented with the cathode-ray tube to create and show images. While working for Westinghouse Electric in 1923, he began to develop an electronic camera tube. However, in a 1925 demonstration, the image was dim, had low contrast and poor definition, and was stationary.[66] Zworykin’s imaging tube never got beyond the laboratory stage. However, RCA, which acquired the Westinghouse patent, asserted that the patent for Farnsworth’s 1927 image dissector was written so broadly that it would exclude any other electronic imaging device. Thus, based on Zworykin’s 1923 patent application, RCA filed a patent interference suit against Farnsworth. The U.S. Patent Office examiner disagreed in a 1935 decision, finding priority of invention for Farnsworth against Zworykin. Farnsworth claimed that Zworykin’s 1923 system could not produce an electrical image of the type to challenge his patent. Zworykin received a patent in 1928 for a color transmission version of his 1923 patent application.[67] He also divided his original application in 1931.[68] Zworykin was unable or unwilling to introduce evidence of a working model of his tube that was based on his 1923 patent application. In September 1939, after losing an appeal in the courts and being determined to go forward with the commercial manufacturing of television equipment, RCA agreed to pay Farnsworth US$1 million over ten years, in addition to license payments, to use his patents.[69][70]

In 1933, RCA introduced an improved camera tube that relied on Tihanyi’s charge storage principle.[71] Called the “Iconoscope” by Zworykin, the new tube had a light sensitivity of about 75,000 lux, and thus was claimed to be much more sensitive than Farnsworth’s image dissector.[citation needed] However, Farnsworth had overcome his power issues with his Image Dissector through the invention of a completely unique “Multipactor” device that he began work on in 1930, and demonstrated in 1931.[72][73] This small tube could amplify a signal reportedly to the 60th power or better[74] and showed great promise in all fields of electronics. Unfortunately, an issue with the multipactor was that it wore out at an unsatisfactory rate.[75]

At the Berlin Radio Show in August 1931 in Berlin, Manfred von Ardenne gave a public demonstration of a television system using a CRT for both transmission and reception, the first completely electronic television transmission.[76] However, Ardenne had not developed a camera tube, using the CRT instead as a flying-spot scanner to scan slides and film.[77] Ardenne achieved his first transmission of television pictures on 24 December 1933, followed by test runs for a public television service in 1934. The world’s first electronically scanned television service then started in Berlin in 1935, the Fernsehsender Paul Nipkow, culminating in the live broadcast of the 1936 Summer Olympic Games from Berlin to public places all over Germany.[78][79]

Philo Farnsworth gave the world’s first public demonstration of an all-electronic television system, using a live camera, at the Franklin Institute of Philadelphia on 25 August 1934 and for ten days afterward.[80][81] Mexican inventor Guillermo González Camarena also played an important role in early television. His experiments with television (known as telectroescopía at first) began in 1931 and led to a patent for the “trichromatic field sequential system” color television in 1940.[82] In Britain, the EMI engineering team led by Isaac Shoenberg applied in 1932 for a patent for a new device they called “the Emitron”,[83][84] which formed the heart of the cameras they designed for the BBC. On 2 November 1936, a 405-line broadcasting service employing the Emitron began at studios in Alexandra Palace and transmitted from a specially built mast atop one of the Victorian building’s towers. It alternated briefly with Baird’s mechanical system in adjoining studios but was more reliable and visibly superior. This was the world’s first regular “high-definition” television service.[85]

The original U.S. iconoscope was noisy, had a high ratio of interference to signal, and ultimately gave disappointing results, especially compared to the high-definition mechanical scanning systems that became available.[86][87] The EMI team, under the supervision of Isaac Shoenberg, analyzed how the iconoscope (or Emitron) produced an electronic signal and concluded that its real efficiency was only about 5% of the theoretical maximum.[88][89] They solved this problem by developing and patenting in 1934 two new camera tubes dubbed super-Emitron and CPS Emitron.[90][91][92] The super-Emitron was between ten and fifteen times more sensitive than the original Emitron and iconoscope tubes, and, in some cases, this ratio was considerably greater.[88] It was used for outside broadcasting by the BBC, for the first time, on Armistice Day 1937, when the general public could watch on a television set as the King laid a wreath at the Cenotaph.[93] This was the first time that anyone had broadcast a live street scene from cameras installed on the roof of neighboring buildings because neither Farnsworth nor RCA would do the same until the 1939 New York World’s Fair.

On the other hand, in 1934, Zworykin shared some patent rights with the German licensee company Telefunken.[94] The “image iconoscope” (“Superikonoskop” in Germany) was produced as a result of the collaboration. This tube is essentially identical to the super-Emitron.[citation needed] The production and commercialization of the super-Emitron and image iconoscope in Europe were not affected by the patent war between Zworykin and Farnsworth because Dieckmann and Hell had priority in Germany for the invention of the image dissector, having submitted a patent application for their Lichtelektrische Bildzerlegerröhre für Fernseher (Photoelectric Image Dissector Tube for Television) in Germany in 1925,[95] two years before Farnsworth did the same in the United States.[96] The image iconoscope (Superikonoskop) became the industrial standard for public broadcasting in Europe from 1936 until 1960, when it was replaced by the vidicon and plumbicon tubes. Indeed, it represented the European tradition in electronic tubes competing against the American tradition represented by the image orthicon.[97][98] The German company Heimann produced the Superikonoskop for the 1936 Berlin Olympic Games,[99][100] later Heimann also produced and commercialized it from 1940 to 1955;[101] finally the Dutch company Philips produced and commercialized the image iconoscope and multicon from 1952 to 1958.[98][102]

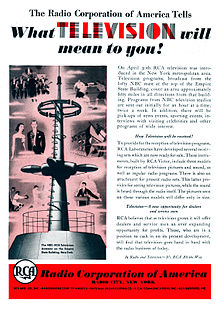

U.S. television broadcasting, at the time, consisted of a variety of markets in a wide range of sizes, each competing for programming and dominance with separate technology until deals were made and standards agreed upon in 1941.[103] RCA, for example, used only Iconoscopes in the New York area, but Farnsworth Image Dissectors in Philadelphia and San Francisco.[104] In September 1939, RCA agreed to pay the Farnsworth Television and Radio Corporation royalties over the next ten years for access to Farnsworth’s patents.[105] With this historic agreement in place, RCA integrated much of what was best about the Farnsworth Technology into their systems.[104] In 1941, the United States implemented 525-line television.[106][107] Electrical engineer Benjamin Adler played a prominent role in the development of television.[108][109]

The world’s first 625-line television standard was designed in the Soviet Union in 1944 and became a national standard in 1946.[110] The first broadcast in 625-line standard occurred in Moscow in 1948.[111] The concept of 625 lines per frame was subsequently implemented in the European CCIR standard.[112] In 1936, Kálmán Tihanyi described the principle of plasma display, the first flat-panel display system.[113][114]

Early electronic television sets were large and bulky, with analog circuits made of vacuum tubes. Following the invention of the first working transistor at Bell Labs, Sony founder Masaru Ibuka predicted in 1952 that the transition to electronic circuits made of transistors would lead to smaller and more portable television sets.[115] The first fully transistorized, portable solid-state television set was the 8-inch Sony TV8-301, developed in 1959 and released in 1960.[116][117] This began the transformation of television viewership from a communal viewing experience to a solitary viewing experience.[118] By 1960, Sony had sold over 4 million portable television sets worldwide.[119]

Color

Main article: Color television

The basic idea of using three monochrome images to produce a color image had been experimented with almost as soon as black-and-white televisions had first been built. Although he gave no practical details, among the earliest published proposals for television was one by Maurice Le Blanc in 1880 for a color system, including the first mentions in television literature of line and frame scanning.[120] Polish inventor Jan Szczepanik patented a color television system in 1897, using a selenium photoelectric cell at the transmitter and an electromagnet controlling an oscillating mirror and a moving prism at the receiver. But his system contained no means of analyzing the spectrum of colors at the transmitting end and could not have worked as he described it.[121] Another inventor, Hovannes Adamian, also experimented with color television as early as 1907. The first color television project is claimed by him,[122] and was patented in Germany on 31 March 1908, patent No. 197183, then in Britain, on 1 April 1908, patent No. 7219,[123] in France (patent No. 390326) and in Russia in 1910 (patent No. 17912).[124]

Scottish inventor John Logie Baird demonstrated the world’s first color transmission on 3 July 1928, using scanning discs at the transmitting and receiving ends with three spirals of apertures, each spiral with filters of a different primary color, and three light sources at the receiving end, with a commutator to alternate their illumination.[125] Baird also made the world’s first color broadcast on 4 February 1938, sending a mechanically scanned 120-line image from Baird’s Crystal Palace studios to a projection screen at London’s Dominion Theatre.[126] Mechanically scanned color television was also demonstrated by Bell Laboratories in June 1929 using three complete systems of photoelectric cells, amplifiers, glow-tubes, and color filters, with a series of mirrors to superimpose the red, green, and blue images into one full-color image.

The first practical hybrid system was again pioneered by John Logie Baird. In 1940 he publicly demonstrated a color television combining a traditional black-and-white display with a rotating colored disk. This device was very “deep” but was later improved with a mirror folding the light path into an entirely practical device resembling a large conventional console.[127] However, Baird was unhappy with the design, and, as early as 1944, had commented to a British government committee that a fully electronic device would be better.

In 1939, Hungarian engineer Peter Carl Goldmark introduced an electro-mechanical system while at CBS, which contained an Iconoscope sensor. The CBS field-sequential color system was partly mechanical, with a disc made of red, blue, and green filters spinning inside the television camera at 1,200 rpm and a similar disc spinning in synchronization in front of the cathode-ray tube inside the receiver set.[128] The system was first demonstrated to the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) on 29 August 1940 and shown to the press on 4 September.[129][130][131][132]

CBS began experimental color field tests using film as early as 28 August 1940 and live cameras by 12 November.[130][133] NBC (owned by RCA) made its first field test of color television on 20 February 1941. CBS began daily color field tests on 1 June 1941.[134] These color systems were not compatible with existing black-and-white television sets, and, as no color television sets were available to the public at this time, viewing of the color field tests was restricted to RCA and CBS engineers and the invited press. The War Production Board halted the manufacture of television and radio equipment for civilian use from 22 April 1942 to 20 August 1945, limiting any opportunity to introduce color television to the general public.[135][136]

As early as 1940, Baird had started work on a fully electronic system he called Telechrome. Early Telechrome devices used two electron guns aimed at either side of a phosphor plate. The phosphor was patterned so the electrons from the guns only fell on one side of the patterning or the other. Using cyan and magenta phosphors, a reasonable limited-color image could be obtained. He also demonstrated the same system using monochrome signals to produce a 3D image (called “stereoscopic” at the time). A demonstration on 16 August 1944 was the first example of a practical color television system. Work on the Telechrome continued, and plans were made to introduce a three-gun version for full color. However, Baird’s untimely death in 1946 ended the development of the Telechrome system.[137][138] Similar concepts were common through the 1940s and 1950s, differing primarily in the way they re-combined the colors generated by the three guns. The Geer tube was similar to Baird’s concept but used small pyramids with the phosphors deposited on their outside faces instead of Baird’s 3D patterning on a flat surface. The Penetron used three layers of phosphor on top of each other and increased the power of the beam to reach the upper layers when drawing those colors. The Chromatron used a set of focusing wires to select the colored phosphors arranged in vertical stripes on the tube.

One of the great technical challenges of introducing color broadcast television was the desire to conserve bandwidth, potentially three times that of the existing black-and-white standards, and not use an excessive amount of radio spectrum. In the United States, after considerable research, the National Television Systems Committee[139] approved an all-electronic system developed by RCA, which encoded the color information separately from the brightness information and significantly reduced the resolution of the color information to conserve bandwidth. As black-and-white televisions could receive the same transmission and display it in black-and-white, the color system adopted is [backwards] “compatible.” (“Compatible Color,” featured in RCA advertisements of the period, is mentioned in the song “America,” of West Side Story, 1957.) The brightness image remained compatible with existing black-and-white television sets at slightly reduced resolution. In contrast, color televisions could decode the extra information in the signal and produce a limited-resolution color display. The higher-resolution black-and-white and lower-resolution color images combine in the brain to produce a seemingly high-resolution color image. The NTSC standard represented a significant technical achievement.

The first color broadcast (the first episode of the live program The Marriage) occurred on 8 July 1954. However, during the following ten years, most network broadcasts and nearly all local programming continued to be black-and-white. It was not until the mid-1960s that color sets started selling in large numbers, due in part to the color transition of 1965, in which it was announced that over half of all network prime-time programming would be broadcast in color that fall. The first all-color prime-time season came just one year later. In 1972, the last holdout among daytime network programs converted to color, resulting in the first completely all-color network season.

Early color sets were either floor-standing console models or tabletop versions nearly as bulky and heavy, so in practice they remained firmly anchored in one place. GE‘s relatively compact and lightweight Porta-Color set was introduced in the spring of 1966. It used a transistor-based UHF tuner.[140] The first fully transistorized color television in the United States was the Quasar television introduced in 1967.[141] These developments made watching color television a more flexible and convenient proposition.

In 1972, sales of color sets finally surpassed sales of black-and-white sets. Color broadcasting in Europe was not standardized on the PAL format until the 1960s, and broadcasts did not start until 1967. By this point, many of the technical issues in the early sets had been worked out, and the spread of color sets in Europe was fairly rapid. By the mid-1970s, the only stations broadcasting in black-and-white were a few high-numbered UHF stations in small markets and a handful of low-power repeater stations in even smaller markets such as vacation spots. By 1979, even the last of these had converted to color. By the early 1980s, B&W sets had been pushed into niche markets, notably low-power uses, small portable sets, or for use as video monitor screens in lower-cost consumer equipment. By the late 1980s, even these last holdout niche B&W environments had inevitably shifted to color sets.

Digital

Main article: Digital television

See also: Digital television transition

Digital television (DTV) is the transmission of audio and video by digitally processed and multiplexed signals, in contrast to the analog and channel-separated signals used by analog television. Due to data compression, digital television can support more than one program in the same channel bandwidth.[142] It is an innovative service that represents the most significant evolution in television broadcast technology since color television emerged in the 1950s.[143] Digital television’s roots have been tied very closely to the availability of inexpensive, high performance computers. It was not until the 1990s that digital television became possible.[144] Digital television was previously not practically possible due to the impractically high bandwidth requirements of uncompressed digital video,[145][146] requiring around 200 Mbit/s for a standard-definition television (SDTV) signal,[145] and over 1 Gbit/s for high-definition television (HDTV).[146]

A digital television service was proposed in 1986 by Nippon Telegraph and Telephone (NTT) and the Ministry of Posts and Telecommunication (MPT) in Japan, where there were plans to develop an “Integrated Network System” service. However, it was not possible to implement such a digital television service practically until the adoption of DCT video compression technology made it possible in the early 1990s.[145]

In the mid-1980s, as Japanese consumer electronics firms forged ahead with the development of HDTV technology, the MUSE analog format proposed by NHK, a Japanese company, was seen as a pacesetter that threatened to eclipse U.S. electronics companies’ technologies. Until June 1990, the Japanese MUSE standard, based on an analog system, was the front-runner among the more than 23 other technical concepts under consideration. Then, a U.S. company, General Instrument, demonstrated the possibility of a digital television signal. This breakthrough was of such significance that the FCC was persuaded to delay its decision on an ATV standard until a digitally-based standard could be developed.

In March 1990, when it became clear that a digital standard was possible, the FCC made several critical decisions. First, the Commission declared that the new ATV standard must be more than an enhanced analog signal but be able to provide a genuine HDTV signal with at least twice the resolution of existing television images. (7) Then, to ensure that viewers who did not wish to buy a new digital television set could continue to receive conventional television broadcasts, it dictated that the new ATV standard must be capable of being “simulcast” on different channels. (8) The new ATV standard also allowed the new DTV signal to be based on entirely new design principles. Although incompatible with the existing NTSC standard, the new DTV standard would be able to incorporate many improvements.

The last standards adopted by the FCC did not require a single standard for scanning formats, aspect ratios, or lines of resolution. This compromise resulted from a dispute between the consumer electronics industry (joined by some broadcasters) and the computer industry (joined by the film industry and some public interest groups) over which of the two scanning processes—interlaced or progressive—would be best suited for the newer digital HDTV compatible display devices.[147] Interlaced scanning, which had been specifically designed for older analog CRT display technologies, scans even-numbered lines first, then odd-numbered ones. Interlaced scanning can be regarded as the first video compression model. It was partly developed in the 1940s to double the image resolution to exceed the limitations of television broadcast bandwidth. Another reason for its adoption was to limit the flickering on early CRT screens, whose phosphor-coated screens could only retain the image from the electron scanning gun for a relatively short duration.[148] However, interlaced scanning does not work as efficiently on newer display devices such as Liquid-crystal (LCD), for example, which are better suited to a more frequent progressive refresh rate.[147]

Progressive scanning, the format that the computer industry had long adopted for computer display monitors, scans every line in sequence, from top to bottom. Progressive scanning, in effect, doubles the amount of data generated for every full screen displayed in comparison to interlaced scanning by painting the screen in one pass in 1/60-second instead of two passes in 1/30-second. The computer industry argued that progressive scanning is superior because it does not “flicker” on the new standard of display devices in the manner of interlaced scanning. It also argued that progressive scanning enables easier connections with the Internet and is more cheaply converted to interlaced formats than vice versa. The film industry also supported progressive scanning because it offered a more efficient means of converting filmed programming into digital formats. For their part, the consumer electronics industry and broadcasters argued that interlaced scanning was the only technology that could transmit the highest quality pictures then (and currently) feasible, i.e., 1,080 lines per picture and 1,920 pixels per line. Broadcasters also favored interlaced scanning because their vast archive of interlaced programming is not readily compatible with a progressive format. William F. Schreiber, who was director of the Advanced Television Research Program at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology from 1983 until his retirement in 1990, thought that the continued advocacy of interlaced equipment originated from consumer electronics companies that were trying to get back the substantial investments they made in the interlaced technology.[149]

Digital television transition started in late 2000s. All governments across the world set the deadline for analog shutdown by the 2010s. Initially, the adoption rate was low, as the first digital tuner-equipped television sets were costly. However, as the price of digital-capable television sets dropped, more and more households started converting to digital television sets. The transition is expected to be completed worldwide by the mid to late 2010s.

Smart television

Main article: Smart television

Not to be confused with Internet television, Internet Protocol television, or Web television.

The advent of digital television allowed innovations like smart television sets. A smart television sometimes referred to as a “connected TV” or “hybrid TV,” is a television set or set-top box with integrated Internet and Web 2.0 features and is an example of technological convergence between computers, television sets, and set-top boxes. Besides the traditional functions of television sets and set-top boxes provided through traditional Broadcasting media, these devices can also provide Internet TV, online interactive media, over-the-top content, as well as on-demand streaming media, and home networking access. These TVs come pre-loaded with an operating system.[10][150][151][152]

Smart TV is not to be confused with Internet TV, Internet Protocol television (IPTV), or with Web TV. Internet television refers to receiving television content over the Internet instead of through traditional systems—terrestrial, cable, and satellite. IPTV is one of the emerging Internet television technology standards for television networks. Web television (WebTV) is a term used for programs created by a wide variety of companies and individuals for broadcast on Internet TV. A first patent was filed in 1994[153] (and extended the following year)[154] for an “intelligent” television system, linked with data processing systems, using a digital or analog network. Apart from being linked to data networks, one key point is its ability to automatically download necessary software routines according to a user’s demand and process their needs. Major TV manufacturers announced the production of smart TVs only for middle-end and high-end TVs in 2015.[7][8][9] Smart TVs have gotten more affordable compared to when they were first introduced, with 46 million U.S. households having at least one as of 2019.[155]

3D

Main article: 3D television

3D television conveys depth perception to the viewer by employing techniques such as stereoscopic display, multi-view display, 2D-plus-depth, or any other form of 3D display. Most modern 3D television sets use an active shutter 3D system or a polarized 3D system, and some are autostereoscopic without the need for glasses. Stereoscopic 3D television was demonstrated for the first time on 10 August 1928, by John Logie Baird in his company’s premises at 133 Long Acre, London.[156] Baird pioneered a variety of 3D television systems using electromechanical and cathode-ray tube techniques. The first 3D television was produced in 1935. The advent of digital television in the 2000s greatly improved 3D television sets. Although 3D television sets are quite popular for watching 3D home media, such as on Blu-ray discs, 3D programming has largely failed to make inroads with the public. As a result, many 3D television channels that started in the early 2010s were shut down by the mid-2010s. According to DisplaySearch 3D television shipments totaled 41.45 million units in 2012, compared with 24.14 in 2011 and 2.26 in 2010.[157] As of late 2013, the number of 3D TV viewers started to decline.[158][159][160][161][162]

Broadcast systems

Terrestrial television

Main article: Terrestrial television

See also: Timeline of the introduction of television in countries

Programming is broadcast by television stations, sometimes called “channels,” as stations are licensed by their governments to broadcast only over assigned channels in the television band. At first, terrestrial broadcasting was the only way television could be widely distributed, and because bandwidth was limited, i.e., there were only a small number of channels available, government regulation was the norm. In the U.S., the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) allowed stations to broadcast advertisements beginning in July 1941 but required public service programming commitments as a requirement for a license. By contrast, the United Kingdom chose a different route, imposing a television license fee on owners of television reception equipment to fund the British Broadcasting Corporation (BBC), which had public service as part of its Royal Charter.

WRGB claims to be the world’s oldest television station, tracing its roots to an experimental station founded on 13 January 1928, broadcasting from the General Electric factory in Schenectady, NY, under the call letters W2XB.[163] It was popularly known as “WGY Television” after its sister radio station. Later, in 1928, General Electric started a second facility, this one in New York City, which had the call letters W2XBS and which today is known as WNBC. The two stations were experimental and had no regular programming, as receivers were operated by engineers within the company. The image of a Felix the Cat doll rotating on a turntable was broadcast for 2 hours every day for several years as engineers tested new technology. On 2 November 1936, the BBC began transmitting the world’s first public regular high-definition service from the Victorian Alexandra Palace in north London.[164] It therefore claims to be the birthplace of television broadcasting as we now know it.

With the widespread adoption of cable across the United States in the 1970s and 1980s, terrestrial television broadcasts have been in decline; in 2013 it was estimated that about 7% of US households used an antenna.[165][166] A slight increase in use began around 2010 due to switchover to digital terrestrial television broadcasts, which offered pristine image quality over very large areas, and offered an alternative to cable television (CATV) for cord cutters. All other countries around the world are also in the process of either shutting down analog terrestrial television or switching over to digital terrestrial television.

Cable television

Main article: Cable television

See also: Cable television by region

Cable television is a system of broadcasting television programming to paying subscribers via radio frequency (RF) signals transmitted through coaxial cables or light pulses through fiber-optic cables. This contrasts with traditional terrestrial television, in which the television signal is transmitted over the air by radio waves and received by a television antenna attached to the television. In the 2000s, FM radio programming, high-speed Internet, telephone service, and similar non-television services may also be provided through these cables. The abbreviation CATV is sometimes used for cable television in the United States. It originally stood for Community Access Television or Community Antenna Television, from cable television’s origins in 1948: in areas where over-the-air reception was limited by distance from transmitters or mountainous terrain, large “community antennas” were constructed, and cable was run from them to individual homes.[167]

Satellite television

Main article: Satellite television

Satellite television is a system of supplying television programming using broadcast signals relayed from communication satellites. The signals are received via an outdoor parabolic reflector antenna, usually referred to as a satellite dish and a low-noise block downconverter (LNB). A satellite receiver then decodes the desired television program for viewing on a television set. Receivers can be external set-top boxes, or a built-in television tuner. Satellite television provides a wide range of channels and services, especially to geographic areas without terrestrial television or cable television.

The most common method of reception is direct-broadcast satellite television (DBSTV), also known as “direct to home” (DTH).[168] In DBSTV systems, signals are relayed from a direct broadcast satellite on the Ku wavelength and are completely digital.[169] Satellite TV systems formerly used systems known as television receive-only. These systems received analog signals transmitted in the C-band spectrum from FSS type satellites and required the use of large dishes. Consequently, these systems were nicknamed “big dish” systems and were more expensive and less popular.[170]

The direct-broadcast satellite television signals were earlier analog signals and later digital signals, both of which require a compatible receiver. Digital signals may include high-definition television (HDTV). Some transmissions and channels are free-to-air or free-to-view, while many other channels are pay television requiring a subscription.[171] In 1945, British science fiction writer Arthur C. Clarke proposed a worldwide communications system that would function by means of three satellites equally spaced apart in Earth orbit.[172][173] This was published in the October 1945 issue of the Wireless World magazine and won him the Franklin Institute‘s Stuart Ballantine Medal in 1963.[174][175]

The first satellite television signals from Europe to North America were relayed via the Telstar satellite over the Atlantic Ocean on 23 July 1962.[176] The signals were received and broadcast in North American and European countries and watched by over 100 million.[176] Launched in 1962, the Relay 1 satellite was the first satellite to transmit television signals from the US to Japan.[177] The first geosynchronous communication satellite, Syncom 2, was launched on 26 July 1963.[178]

The world’s first commercial communications satellite, called Intelsat I and nicknamed “Early Bird”, was launched into geosynchronous orbit on 6 April 1965.[179] The first national network of television satellites, called Orbita, was created by the Soviet Union in October 1967, and was based on the principle of using the highly elliptical Molniya satellite for rebroadcasting and delivering of television signals to ground downlink stations.[180] The first commercial North American satellite to carry television transmissions was Canada’s geostationary Anik 1, which was launched on 9 November 1972.[181] ATS-6, the world’s first experimental educational and Direct Broadcast Satellite (DBS), was launched on 30 May 1974.[182] It transmitted at 860 MHz using wideband FM modulation and had two sound channels. The transmissions were focused on the Indian subcontinent, but experimenters were able to receive the signal in Western Europe using home-constructed equipment that drew on UHF television design techniques already in use.[183]

The first in a series of Soviet geostationary satellites to carry Direct-To-Home television, Ekran 1, was launched on 26 October 1976.[184] It used a 714 MHz UHF downlink frequency so that the transmissions could be received with existing UHF television technology rather than microwave technology.[185]

Internet television

Main article: Streaming television

Not to be confused with Smart television, Internet Protocol television, or Web television.

Internet television (Internet TV) (or online television) is the digital distribution of television content via the Internet as opposed to traditional systems like terrestrial, cable, and satellite, although the Internet itself is received by terrestrial, cable, or satellite methods. Internet television is a general term that covers the delivery of television series and other video content over the Internet by video streaming technology, typically by major traditional television broadcasters. Internet television should not be confused with Smart TV, IPTV, or with Web TV. Smart television refers to the television set which has a built-in operating system. Internet Protocol television (IPTV) is one of the emerging Internet television technology standards for use by television networks. Web television is a term used for programs created by a wide variety of companies and individuals for broadcast on Internet television.

Traditional cable and satellite television providers began to offer services such as Sling TV, owned by Dish Network, which was unveiled in January 2015.[186] DirecTV, another satellite television provider, launched their own streaming service, DirecTV Stream, in 2016.[187][188] Sky launched a similar streaming service in the UK called Now. In 2013, Video on demand website Netflix earned the first Primetime Emmy Award nominations for original streaming television at the 65th Primetime Emmy Awards. Three of its series, House of Cards, Arrested Development, and Hemlock Grove, earned nominations that year.[189] On July 13, 2015, cable company Comcast announced an HBO plus broadcast TV package at a price discounted from basic broadband plus basic cable.[190]

In 2017, YouTube launched YouTube TV, a streaming service that allows users to watch live television programs from popular cable or network channels and record shows to stream anywhere, anytime.[191][192][193] As of 2017, 28% of US adults cite streaming services as their main means for watching television, and 61% of those ages 18 to 29 cite it as their main method.[194][195] As of 2018, Netflix is the world’s largest streaming TV network and also the world’s largest Internet media and entertainment company with 117 million paid subscribers, and by revenue and market cap.[196][197] In 2020, the COVID-19 pandemic had a strong impact in the television streaming business with the lifestyle changes such as staying at home and lockdowns.[198][199][200][201]

Sets

Main article: Television set

A television set, also called a television receiver, television, TV set, TV, or “telly,” is a device that combines a tuner, display, amplifier, and speakers for the purpose of viewing television and hearing its audio components. Introduced in the late 1920s in mechanical form, television sets became a popular consumer product after World War II in electronic form, using cathode-ray tubes. The addition of color to broadcast television after 1953 further increased the popularity of television sets, and an outdoor antenna became a common feature of suburban homes. The ubiquitous television set became the display device for recorded media in the 1970s, such as Betamax and VHS, which enabled viewers to record TV shows and watch prerecorded movies. In the subsequent decades, Television sets were used to watch DVDs and Blu-ray Discs of movies and other content. Major TV manufacturers announced the discontinuation of CRT, DLP, plasma, and fluorescent-backlit LCDs by the mid-2010s. Televisions since 2010s mostly use LEDs.[4][5][202][203] LEDs are expected to be gradually replaced by OLEDs in the near future.[6]

Display technologies

Main article: Display device

Disk

Main article: Nipkow disk

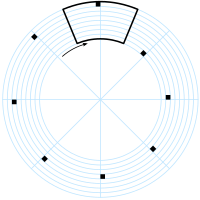

The earliest systems employed a spinning disk to create and reproduce images.[204] These usually had a low resolution and screen size and never became popular with the public.

CRT

Main article: Cathode-ray tube

The cathode-ray tube (CRT) is a vacuum tube containing one or more electron guns (a source of electrons or electron emitter) and a fluorescent screen used to view images.[38] It has the means to accelerate and deflect the electron beam(s) onto the screen to create the images. The images may represent electrical waveforms (oscilloscope), pictures (television, computer monitor), radar targets or others. The CRT uses an evacuated glass envelope that is large, deep (i.e., long from front screen face to rear end), fairly heavy, and relatively fragile. As a matter of safety, the face is typically made of thick lead glass so as to be highly shatter-resistant and to block most X-ray emissions, particularly if the CRT is used in a consumer product.

In television sets and computer monitors, the entire front area of the tube is scanned repetitively and systematically in a fixed pattern called a raster. An image is produced by controlling the intensity of each of the three electron beams, one for each additive primary color (red, green, and blue) with a video signal as a reference.[205] In all modern CRT monitors and televisions, the beams are bent by magnetic deflection, a varying magnetic field generated by coils and driven by electronic circuits around the neck of the tube, although electrostatic deflection is commonly used in oscilloscopes, a type of diagnostic instrument.[205]

DLP

Main article: Digital Light Processing

Digital Light Processing (DLP) is a type of video projector technology that uses a digital micromirror device. Some DLPs have a TV tuner, which makes them a type of TV display. It was originally developed in 1987 by Dr. Larry Hornbeck of Texas Instruments. While the DLP imaging device was invented by Texas Instruments, the first DLP-based projector was introduced by Digital Projection Ltd in 1997. Digital Projection and Texas Instruments were both awarded Emmy Awards in 1998 for the invention of the DLP projector technology. DLP is used in a variety of display applications, from traditional static displays to interactive displays and also non-traditional embedded applications, including medical, security, and industrial uses. DLP technology is used in DLP front projectors (standalone projection units for classrooms and businesses primarily) but also in private homes; in these cases, the image is projected onto a projection screen. DLP is also used in DLP rear projection television sets and digital signs. It is also used in about 85% of digital cinema projection.[206]

Plasma

Main article: Plasma display

A plasma display panel (PDP) is a type of flat-panel display common to large television displays 30 inches (76 cm) or larger. They are called “plasma” displays because the technology uses small cells containing electrically charged ionized gases, or what are in essence chambers more commonly known as fluorescent lamps.

LCD

Main article: Liquid-crystal display

Liquid-crystal-display televisions (LCD TVs) are television sets that use liquid-crystal display technology to produce images. LCD televisions are much thinner and lighter than cathode-ray tube (CRTs) of similar display size and are available in much larger sizes (e.g., 90-inch diagonal). When manufacturing costs fell, this combination of features made LCDs practical for television receivers. LCDs come in two types: those using cold cathode fluorescent lamps, simply called LCDs, and those using LED as backlight called LEDs.

In 2007, LCD television sets surpassed sales of CRT-based television sets worldwide for the first time, and their sales figures relative to other technologies accelerated. LCD television sets have quickly displaced the only major competitors in the large-screen market, the Plasma display panel and rear-projection television.[207] In mid 2010s LCDs especially LEDs became, by far, the most widely produced and sold television display type.[202][203] LCDs also have disadvantages. Other technologies address these weaknesses, including OLEDs, FED and SED, but as of 2014 none of these have entered widespread production.

OLED

Main article: OLED

An OLED (organic light-emitting diode) is a light-emitting diode (LED) in which the emissive electroluminescent layer is a film of organic compound which emits light in response to an electric current. This layer of organic semiconductor is situated between two electrodes. Generally, at least one of these electrodes is transparent. OLEDs are used to create digital displays in devices such as television screens. It is also used for computer monitors and portable systems such as mobile phones, handheld game console, and PDAs.

There are two main groups of OLED: those based on small molecules and those employing polymers. Adding mobile ions to an OLED creates a light-emitting electrochemical cell or LEC, which has a slightly different mode of operation. OLED displays can use either passive-matrix (PMOLED) or active-matrix (AMOLED) addressing schemes. Active-matrix OLEDs require a thin-film transistor backplane to switch each individual pixel on or off but allow for higher resolution and larger display sizes.

An OLED display works without a backlight. Thus, it can display deep black levels and can be thinner and lighter than a liquid crystal display (LCD). In low ambient light conditions such as a dark room, an OLED screen can achieve a higher contrast ratio than an LCD, whether the LCD uses cold cathode fluorescent lamps or LED backlight. OLEDs are expected to replace other forms of display in the near future.[6]

Display resolution

LD

Main article: Low-definition television

Low-definition television or LDTV refers to television systems that have a lower screen resolution than standard-definition television systems such 240p (320*240). It is used in handheld television. The most common source of LDTV programming is the Internet, where mass distribution of higher-resolution video files could overwhelm computer servers and take too long to download. Many mobile phones and portable devices such as Apple‘s iPod Nano, or Sony’s PlayStation Portable use LDTV video, as higher-resolution files would be excessive to the needs of their small screens (320×240 and 480×272 pixels respectively). The current generation of iPod Nanos has LDTV screens, as do the first three generations of iPod Touch and iPhone (480×320). For the first years of its existence, YouTube offered only one low-definition resolution of 320x240p at 30fps or less. A standard, consumer-grade videotape can be considered SDTV due to its resolution (approximately 360 × 480i/576i).

SD

Main article: Standard-definition television

Standard-definition television or SDTV refers to two different resolutions: 576i, with 576 interlaced lines of resolution, derived from the European-developed PAL and SECAM systems, and 480i based on the American National Television System Committee NTSC system. SDTV is a television system that uses a resolution that is not considered to be either high-definition television (720p, 1080i, 1080p, 1440p, 4K UHDTV, and 8K UHD) or enhanced-definition television (EDTV 480p). In North America, digital SDTV is broadcast in the same 4:3 aspect ratio as NTSC signals, with widescreen content being center cut.[208] However, in other parts of the world that used the PAL or SECAM color systems, standard-definition television is now usually shown with a 16:9 aspect ratio, with the transition occurring between the mid-1990s and mid-2000s. Older programs with a 4:3 aspect ratio are shown in the United States as 4:3, with non-ATSC countries preferring to reduce the horizontal resolution by anamorphically scaling a pillarboxed image.

HD

Main article: High-definition television

High-definition television (HDTV) provides a resolution that is substantially higher than that of standard-definition television.

HDTV may be transmitted in various formats:

- 1080p: 1920×1080p: 2,073,600 pixels (~2.07 megapixels) per frame

- 1080i: 1920×1080i: 1,036,800 pixels (~1.04 MP) per field or 2,073,600 pixels (~2.07 MP) per frame

- A non-standard CEA resolution exists in some countries such as 1440×1080i: 777,600 pixels (~0.78 MP) per field or 1,555,200 pixels (~1.56 MP) per frame

- 720p: 1280×720p: 921,600 pixels (~0.92 MP) per frame

UHD

Main article: Ultra-high-definition television

Ultra-high-definition television (also known as Super Hi-Vision, Ultra HD television, UltraHD, UHDTV, or UHD) includes 4K UHD (2160p) and 8K UHD (4320p), which are two digital video formats proposed by NHK Science & Technology Research Laboratories and defined and approved by the International Telecommunication Union (ITU). The Consumer Electronics Association announced on 17 October 2012 that “Ultra High Definition,” or “Ultra HD,” would be used for displays that have an aspect ratio of at least 16:9 and at least one digital input capable of carrying and presenting natural video at a minimum resolution of 3840×2160 pixels.[209][210]

Market share

North American consumers purchase a new television set on average every seven years, and the average household owns 2.8 televisions. As of 2011, 48 million are sold each year at an average price of $460 and size of 38 in (97 cm).[211]

| Worldwide TV manufacturers market share, H1 2023 | ||

|---|---|---|

| Manufacturer | Market share[212] | |

| Samsung Electronics | 31.2% | |

| LG Electronics | 16.2% | |

| TCL | 10.2% | |

| Hisense | 9.5% | |

| Sony | 5.7% | |

| Others | 39% | |

Content

Programming

See also: Television show, Video production, and Television studio

Getting TV programming shown to the public can happen in many other ways. After production, the next step is to market and deliver the product to whichever markets are open to using it. This typically happens on two levels:

- Original run or First run: a producer creates a program of one or multiple episodes and shows it on a station or network that has either paid for the production itself or granted a license by the television producers to do the same.

- Broadcast syndication: this is the terminology rather broadly used to describe secondary programming usages (beyond the original run). It includes secondary runs in the country of the first issue, but also international usage, which may not be managed by the originating producer. In many cases, other companies, television stations, or individuals are engaged to do the syndication work, in other words, to sell the product into the markets they are allowed to sell into by contract from the copyright holders; in most cases, the producers.

First-run programming is increasing on subscription services outside of the United States, but few domestically produced programs are syndicated on domestic free-to-air (FTA) elsewhere. This practice is increasing, however, generally on digital-only FTA channels or with subscriber-only, first-run material appearing on FTA. Unlike the United States, repeat FTA screenings of an FTA network program usually only occur on that network. Also, affiliates rarely buy or produce non-network programming that is not focused on local programming.

Genres

| The examples and perspective in this section deal primarily with the United States and do not represent a worldwide view of the subject. You may improve this section, discuss the issue on the talk page, or create a new section, as appropriate. (December 2014) (Learn how and when to remove this message) |

Television genres include a broad range of programming types that entertain, inform, and educate viewers. The most expensive entertainment genres to produce are usually dramas and dramatic miniseries. However, other genres, such as historical Western genres, may also have high production costs.

Pop culture entertainment genres include action-oriented shows such as police, crime, detective dramas, horror, or thriller shows. As well, there are also other variants of the drama genre, such as medical dramas and daytime soap operas. Sci-fi series can fall into either the drama or action category, depending on whether they emphasize philosophical questions or high adventure. Comedy is a popular genre that includes situation comedy (sitcom) and animated series for the adult demographic, such as Comedy Central’s South Park.

The least expensive forms of entertainment programming genres are game shows, talk shows, variety shows, and reality television. Game shows feature contestants answering questions and solving puzzles to win prizes. Talk shows contain interviews with film, television, music, and sports celebrities and public figures. Variety shows feature a range of musical performers and other entertainers, such as comedians and magicians, introduced by a host or Master of Ceremonies. There is some crossover between some talk shows and variety shows because leading talk shows often feature performances by bands, singers, comedians, and other performers in between the interview segments. Reality television series “regular” people (i.e., not actors) facing unusual challenges or experiences ranging from arrest by police officers (COPS) to significant weight loss (The Biggest Loser). A derived version of reality shows depicts celebrities doing mundane activities such as going about their everyday life (The Osbournes, Snoop Dogg’s Father Hood) or doing regular jobs (The Simple Life).[213]

Fictional television programs that some television scholars and broadcasting advocacy groups argue are “quality television“, include series such as Twin Peaks and The Sopranos. Kristin Thompson argues that some of these television series exhibit traits also found in art films, such as psychological realism, narrative complexity, and ambiguous plotlines. Nonfiction television programs that some television scholars and broadcasting advocacy groups argue are “quality television” include a range of serious, noncommercial programming aimed at a niche audience, such as documentaries and public affairs shows.

Funding

Around the world, broadcast television is financed by government, advertising, licensing (a form of tax), subscription, or any combination of these. To protect revenues, subscription television channels are usually encrypted to ensure that only subscribers receive the decryption codes to see the signal. Unencrypted channels are known as free-to-air or FTA. In 2009, the global TV market represented 1,217.2 million TV households with at least one TV and total revenues of 268.9 billion EUR (declining 1.2% compared to 2008).[214] North America had the biggest TV revenue market share with 39% followed by Europe (31%), Asia-Pacific (21%), Latin America (8%), and Africa and the Middle East (2%).[215] Globally, the different TV revenue sources are divided into 45–50% TV advertising revenues, 40–45% subscription fees, and 10% public funding.[216][217]

Advertising

Main article: Television advertisement

Television’s broad reach makes it a powerful and attractive medium for advertisers. Many television networks and stations sell blocks of broadcast time to advertisers (“sponsors”) to fund their programming.[218] Television advertisements (variously called a television commercial, commercial, or ad in American English, and known in British English as an advert) is a span of television programming produced and paid for by an organization, which conveys a message, typically to market a product or service. Advertising revenue provides a significant portion of the funding for most privately owned television networks. The vast majority of television advertisements today consist of brief advertising spots, ranging in length from a few seconds to several minutes (as well as program-length infomercials). Advertisements of this sort have been used to promote a wide variety of goods, services, and ideas since the beginning of television.

The effects of television advertising upon the viewing public (and the effects of mass media in general) have been the subject of discourse by philosophers, including Marshall McLuhan. The viewership of television programming, as measured by companies such as Nielsen Media Research, is often used as a metric for television advertisement placement and, consequently, for the rates charged to advertisers to air within a given network, television program, or time of day (called a “daypart”). In many countries, including the United States, television campaign advertisements is considered indispensable for a political campaign. In other countries, such as France, political advertising on television is heavily restricted,[219] while some countries, such as Norway, completely ban political advertisements.

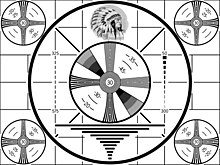

The first official, paid television advertisement was broadcast in the United States on 1 July 1941, over New York station WNBT (now WNBC) before a baseball game between the Brooklyn Dodgers and Philadelphia Phillies. The announcement for Bulova watches, for which the company paid anywhere from $4.00 to $9.00 (reports vary), displayed a WNBT test pattern modified to look like a clock with the hands showing the time. The Bulova logo, with the phrase “Bulova Watch Time,” was shown in the lower right-hand quadrant of the test pattern while the second hand swept around the dial for one minute.[220][221] The first TV ad broadcast in the U.K. was on ITV on 22 September 1955, advertising Gibbs SR toothpaste. The first TV ad broadcast in Asia was on Nippon Television in Tokyo on 28 August 1953, advertising Seikosha (now Seiko), which also displayed a clock with the current time.[222]

United States

Since inception in the US in 1941,[223] television commercials have become one of the most effective, persuasive, and popular methods of selling products of many sorts, especially consumer goods. During the 1940s and into the 1950s, programs were hosted by single advertisers. This, in turn, gave great creative control to the advertisers over the content of the show. Perhaps due to the quiz show scandals in the 1950s,[224] networks shifted to the magazine concept, introducing advertising breaks with other advertisers.

U.S. advertising rates are determined primarily by Nielsen ratings. The time of the day and popularity of the channel determine how much a TV commercial can cost. For example, it can cost approximately $750,000 for a 30-second block of commercial time during the highly popular singing competition American Idol, while the same amount of time for the Super Bowl can cost several million dollars. Conversely, lesser-viewed time slots, such as early mornings and weekday afternoons, are often sold in bulk to producers of infomercials at far lower rates. In recent years, paid programs or infomercials have become common, usually in lengths of 30 minutes or one hour. Some drug companies and other businesses have even created “news” items for broadcast, known in the industry as video news releases, paying program directors to use them.[225]

Some television programs also deliberately place products into their shows as advertisements, a practice started in feature films[226] and known as product placement. For example, a character could be drinking a certain kind of soda, going to a particular chain restaurant, or driving a certain make of car. (This is sometimes very subtle, with shows having vehicles provided by manufacturers for low cost in exchange as a product placement). Sometimes, a specific brand or trade mark, or music from a certain artist or group, is used. (This excludes guest appearances by artists who perform on the show.)

United Kingdom